The M-30 South bypass is one of the country’s busiest stretches of road. This article explains its history and evolution in order to understand its usefulness as well as how it works.

The M-30 is a benchmark for mobility in the Spanish capital. It is a ring road around the city with the characteristics of a motorway. Except in the north section of Avenida de la Ilustración, where traffic is controlled by traffic lights.

Like any other large twentieth century city, due to population growth and constantly increasing vehicle numbers, the origin of ring roads in the city of Madrid can be traced back to two urban plans in particular:

Construction of the M-30 got underway in 1970. And over the next four years, the first two sections were built: the east part (between the roads of Irún and Andalucía) and the west section (from Puente de los Franceses to the current A-4). The two roads joined at the South Junction; the northern closure of the M-30 that occurred in the 1990s.

In the Council of Ministers, on 20 February, 2004, ownership of the M-30 was definitively granted to Madrid City Council. Sections converted to urban areas that, until then, were dependent on the Ministry of Development.

This assignment allowed the City Council to execute the Madrid Calle 30 project, the road’s current name. This road’s design led to the interior of the city being named the “central almond” referring to its circular road in the shape of an oval.

When a large part of the traffic movements of the city coincided in the South Junction, for Madrid, that particular section of the M-30 was the area with the highest density and mobility problems.

Before the construction of the bypass, the problem was having to go between an excessive number of entrances and exits to and from the bypass’ trunk road.

The complexity in the Junction links and the many short weaving stretches meant that section of the M-30 was on the brink of being brought to a standstill for a good part of the day.

Pollution and the high number of accidents made it necessary for civil engineering to intervene. The objectives were clear:

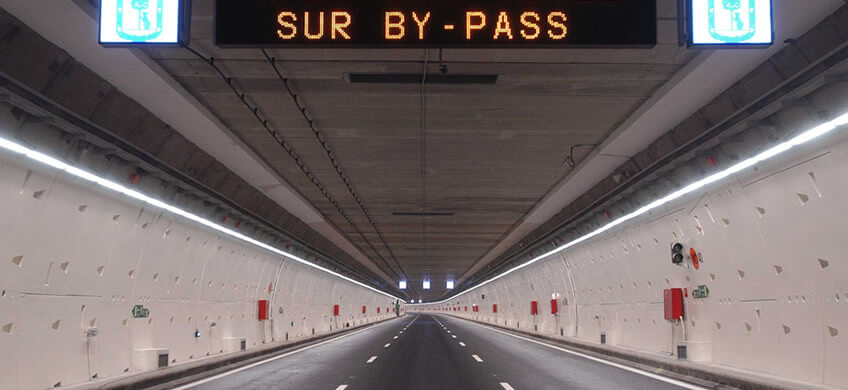

The south bypass is formed by two unidirectional twin tunnels: north and south. Both are 4.2 km long, and have been in service since 2007. In both cases they are a fundamental part of all the west-east traffic. They are connected to the underground section that runs parallel along the Manzanares River.

It is 4.28 km long and was executed using a tunneling machine. It is next to Palacio de Cristal (Glass Palace), starting in the Manzanares tunnels at the Praga Bridge and finishing east of the M-30 towards Conde de Casal. Furthermore, it has an exit to the A-3 road in the direction of Valencia.

There are numerous accesses to the south tunnel. Among them, an entrance connected directly from Marqués de Vadillo and another located next to the old Vicente Calderón stadium, about 200 metres from the Toledo bridge. This directs the traffic from the roads of Extremadura and A Coruña.

It has three lanes which are each 3.50 m wide, with 1 m footpaths on both sides.

This tunnel is 4.20 km of the M-30 between the A-3, at Conde de Casal and Paseo de Santa María de la Cabeza.

It has three 3.50 m lanes, and 1 m wide footpaths.

The tunnels of the south bypass free traffic to the South Junction. Below the Arganzuela and Tierno Galván parks, they speed up the west routes towards the A-3 and the traffic that is directed to carretera de Andalusia road from the A-42 and Avenida del Mediterráneo.

With this, almost 42% of the traffic in the southern arch of the M-30 has been eliminated. In addition, accidents and pollution have been significantly reduced. Both the long-distance traffic within the city, and traffic going to any point in the area has also been reorganized.

To sum up, it is safe to say that the south bypass has directed the through traffic in both directions between east and the west of the M-30. Being the best underground alternative to previous overground roads.